The Story of John Fogerty’s Lengthy Path to ‘Centerfield’

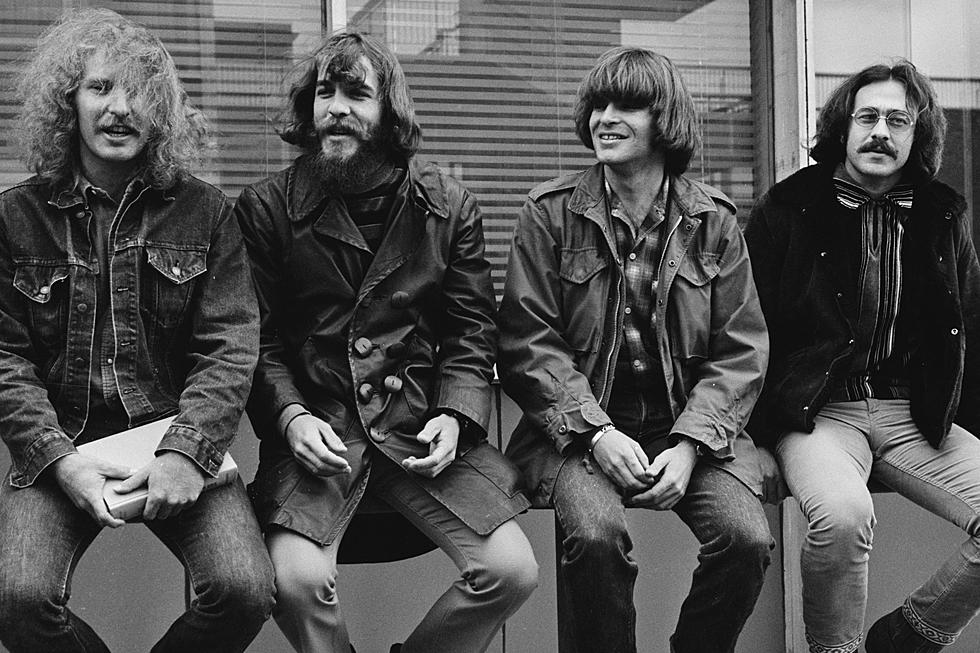

former Creedence Clearwater Revival frontman John Fogerty returned with his fourth solo LP, Centerfield, on Jan. 16, 1985, roughly a decade after he'd last released an album of new material.

Happy as fans were to hear from him, everyone wanted to know the same thing: Where had he been?

As with anything that takes 10 years, Fogerty's hiatus was due to a number of things – the first of which was the rejection of what was supposed to be his fourth solo outing, then titled Hoodoo, in 1976. Instead of leaning on him to deliver something better, Elektra chief Joe Smith told Fogerty to take his time and come back when he was ready – a stunning turn of events for a performer who'd always felt pressure, both internal and from his label, to churn out hit product on a regular basis.

"That was the greatest thing that ever happened," Fogerty told BAM in 1985, acknowledging that Smith's gentle rejection helped him get past what he deemed "a lot of problems." As he put it, "The first thing I decided was I could take the time to have taste again, you know, the way it was before, when nothing came out until it was ready."

Meanwhile, Fogerty found himself embroiled in a nasty, drawn-out legal war over Creedence Clearwater Revival's legacy and the disbursement of contested royalties – a parade of lawyers and divided royalties that he admitted sent him spiraling into a terrible case of writer's block.

Listen to John Fogerty Perform 'Rock and Roll Girls'

"I would see these people's faces in front of me, holding big bags of money they'd gotten from us, like a specter, a hallucination," he recalled. And although he ended up spending untold hours practicing in the studio – time he said helped him sharpen his chops considerably – he wasn't sure where all that work would ever lead. "It was getting worse, more and more depressed, and further away from the center of John Fogerty. I could play but I didn't know what to play. ... A blind man in a fog, just flitting around."

The song that ultimately snapped John Fogerty's dry streak was 'I Saw It on TV,' a track that became a cornerstone of the nine-song Centerfield. Recalling that he'd "thought about this song for three or four years, with just a verse, and a smattering of melody," he traced its watershed moment to a fishing trip that left him with a day of nothing but drifting and thinking on his hands.

"I quit about six o'clock in the evening and walked back to the car with maybe a verse-and-a-half and a chorus. I was starting to feel a little confident. And I got my fishing gear straight and shut the door in the car and CLICK – my brain said 'Hey, I can do this!' It felt like before, when I'd give myself that certain space and write ‘Proud Mary’ or whatever," he continued. "I had jumped over the hurdle. I was a songwriter again. It was a great moment for me."

That moment helped launch John Fogerty past a crucible that nearly warped his childhood dream beyond repair. "Our goal was to be like Elvis [Presley] or Little Richard in eighth and ninth grade, and we came up from El Cerrito and we succeeded, and we're traveling around the world in Lear jets," he pointed out. "And then suddenly I found myself chained to the dungeon wall, and I was cranking out little gems to pay for the cost of keeping a guard on my door."

Watch John Fogerty Perform 'The Old Man Down the Road'

With "I Saw It on TV" under his belt, Fogerty was back in business as a songwriter, but that didn't mean he was back to cranking out classics at the same speed he had during Creedence Clearwater Revival's glory days. The album that would eventually become Centerfield came together slowly – partly due to Fogerty's commitment to detail, and partly because he simply wasn't sure what he should sound like anymore.

Finally, after toying with various approaches, he "drop-kicked the keyboards out the window" and more or less made his way back to where he started. Many critics pointed out that 'Centerfield' sounded a lot like a Creedence record.

It's a similarity that might have seemed like a cynical cop-out, if CCR's rootsy approach was still paying dividends on the synth-coated Top 40 of the mid-'80s. But it actually served as a sign that after years of struggling to put it behind him, one of rock's greatest songwriters was starting to come to terms with his past.

It was a slow process, however. "I knew it sounded like Creedence, and I wondered if Warners thought they were getting Michael Jackson or some modern synth-rock," Fogerty later admitted. "I had to find out if I was working on the right thing. It was like in The Shining, when you think the guy is working on a book, but all he's been doing is typing the same line over and over. I thought maybe I was out there somewhere, lost."

Listen to John Fogerty's 'Centerfield'

If the label's enthusiasm reinforced those first steps, then the public's response to Centerfield took John Fogerty the rest of the way. A hit beyond anyone's wildest expectations, the album rose all the way to No. 1 on the Billboard album chart, and sent leadoff single "The Old Man Down the Road" to No. 10 on the Hot 100. A follow-up, "Rock and Roll Girls," hit No. 20; the title track, a No. 4 rock hit, stalled just outside the pop Top 40.

Initially, it seemed like the success of Centerfield might have signaled the opening of a creative logjam that could trigger a flood of new material approaching Fogerty's legendarily prolific pace with Creedence Clearwater Revival; the following October, he followed it up with another solo effort, Eye of the Zombie. Unfortunately, that album led into another lengthy break that lasted nearly as long as the one before Centerfield – but this time, Fogerty had really started to make peace with his turbulent creative past, and begun to appreciate his own place in the rock firmament.

"There's this guy buried there, and maybe some guy named Morris Stealum of Cheatem, Beatem & Whatever owns [his] songs in some big building in Manhattan," Fogerty later mused in an interview with Rolling Stone, recounting a visit to Robert Johnson's grave. Reminded of his own fight with Fantasy Records boss Saul Zaentz for control of his earlier songs, he couldn't resist drawing a parallel – and a line in the sand.

"It's Robert [Johnson] who owns those songs; he's the spiritual owner of those songs. Muddy [Waters] owns his songs; Howlin' Wolf owns his songs," Fogerty said. "And someday, somebody is gonna be standing where I'm buried, and they won't know about Saul Zaentz – screw him. What they'll know is if they thought the life's work was valuable or not. Standing among all those giants, I went, 'That's the deal here. It's time to jump back into your own stream.'"

Final Albums: 41 of Rock's Most Memorable Farewells

More From Ultimate Classic Rock