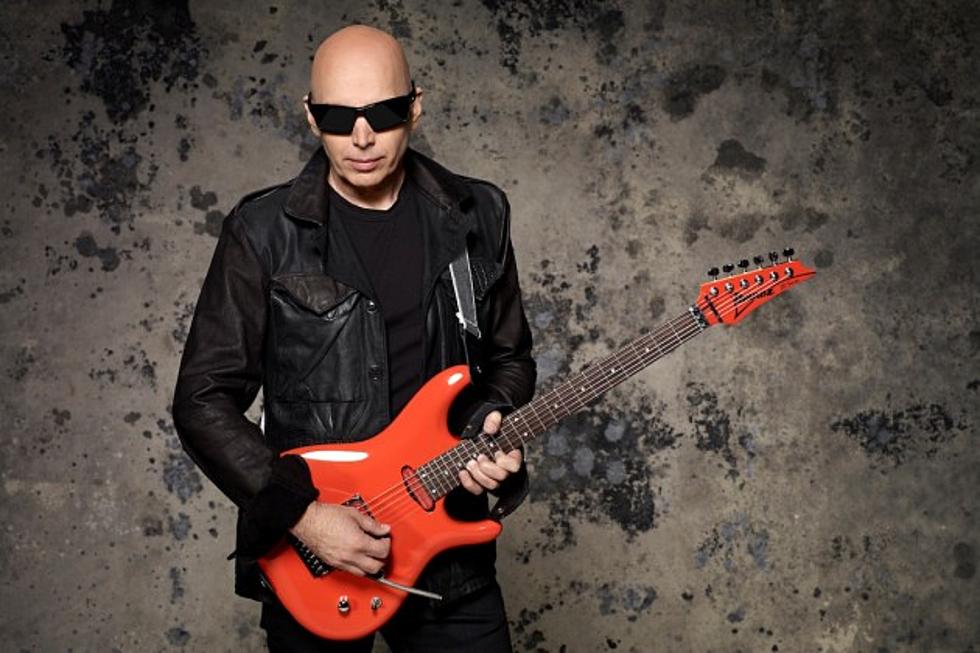

Joe Satriani Takes Us Inside His ‘Shockwave Supernova’

Ultimate Classic Rock recently premiered new music from Joe Satriani’s upcoming album, Shockwave Supernova, which lands in stores on July 24.

As is always the case, there’s quite a story attached to how Satriani brought Shockwave Supernova to life. It started with a huge batch of songs that he wrote while he was sidelined with the H1N1 virus, a time period that produced over 100 song ideas. But as you’ll read below, that was only the beginning of the events that eventually left the veteran guitarist with a fresh addition to his discography.

Now he’s tuning up for another massive world tour to share the new music with the masses. We spoke with him in advance of all of that to find out the latest things that are making his world tick.

As I understand it, the seeds for this new album begin with you onstage, realizing how much you’ve been playing guitar with your teeth. That’s one of the more interesting creative entry points I’ve heard in a while.

[Laughs] I know, it is kind of funny. Somewhere along the line, I guess with the beginning of the Unstoppable [Momentum] tour, I guess there were just more moments where that was happening. I was playing more with Mike Keneally, like the two of us would be out there just freely jamming all of the time, you know, trading solos. And you know, he’s so damn good that I guess sometimes I just wind up answering back some crazy lead with playing with my teeth. So as we’re winding up and getting to the end of this long tour, I start to notice that my teeth did not feel the same anymore.

My front two teeth were feeling like someone had been scraping the tips off and I thought, “Well, I know who’s been doing that.” It’s this alter-ego, whoever takes over when I’m onstage and is willing to do something stupid just to make the moment more fun and rock and roll. So we were walking out onstage at the last show in Singapore and I thought, “You know what? Tonight, that’s it. I’m not going to do this anymore.” And then about 25 minutes later, there I am, just down on my knees and playing with my teeth. [Laughs] A little voice in my head said, “This is the last time!”

We hung out in Singapore for about a week after the end of the tour and I started to really think about that whole process and how humorous it was. I had been collecting all of this material for the album and it started to dawn on me that the music I was writing really could be tied to the idea that this alter ego of mine, who I then named “Shockwave Supernova,” you know….of course a personality like that would insist on some ridiculous name like that. I thought, you know, the record has to be the story about how the real person, Joe, wrestles with this guy and says, “You know what? It’s time for you to move on.” [Laughs]

And so Shockwave goes through all of this reminiscing and soul searching about his whole career, represented by all of the different kinds of material on the record, and then in the end he realizes he’s not being retired, he’s not dying -- he’s actually being reborn into something better -- and that’s what the last track is all about. Of course, you know, you have to imagine that every time I’d think about this, I’d get excited and then I’d go, “Oh, I must be out of my mind. This is ridiculous.” I had to run it by my wife first and then my manager and then eventually, I sat down with the guys at Sony/Legacy -- but everyone seemed to think it was a great idea and so I got the green light to do this 15-song epic project and I’m so happy they let me do it.

It was so liberating to be able to have such a huge canvas to work with this time. It just allowed me to play more and show people all of the different sides of my playing and what I’ve been working on and what I’ve been developing. So from a guitar player’s point of view, it was a neverending festival that I was at the center of. [Laughs] I had such a great time doing it.

That story seems like it could almost be a little bit autobiographical in a sense, because there’s no doubt that this far into your career, you’ve probably wrestled with a number of the elements that you stuck into the story.

Absolutely, yes. You know, some of them are very serious and some of them are complete fantasy and some of them are just funny, you know, just like poking fun. Here’s a funny anecdote -- there’s a song called “A Phase I’m Going Through” and it had the most unlikely start, right? I think it started out as a little idea for a Chickenfoot song and I lost it -- it was just sitting in a folder somewhere on my computer. I had come across it one day and I’m listening to it and I go, “Why did I ever think Sammy [Hagar] would sing anything like this?” You know, it’s like, it’s silly.

But I’m listening to it and I’m going, that’s kind of cool. So I just started to develop it and I go, “Oh, this is really a cool song, because it’s actually a bit more emotionally deep.” But at the same time, it’s got this sort of funny, upbeat [feeling] -- the chord sequence was playful. So I got interrupted while I was making the demo with a phone call from my co-producer and engineer, John Cuniberti, and we started talking about a remix he did of “Scarborough Stomp,” which he had taken one of the solo bits and put it through a heavy phasing. You have to understand that John and I go way back, right? We’ve been working since 1980.

Even as far back as us mixing the Surfing [With the Alien] record, we would always grapple with whether or not to use phasing, because it was like a joke. Like, when you’re in the studio, you think the phaser is the coolest thing ever and then three weeks later, you go, “Why did I use the phaser! That’s the cheesiest thing ever!” So it came up again, but I said, “You know what? John, I heard the phaser and I started laughing to myself because of our history with using phasing, but then I said, you know what? I’m going to be contrarian about this -- I’m just going to say phaser used to be bad and now I’m going to say, phaser is good.” So I said, “I love your remix it, let’s just leave it alone.” And then I go back to the demo and I’m looking at this thing and I said, “You know what? I’m going to phase everything!”

Suddenly, the song came into focus and I printed a version of it with this heavy Mutron Bi-Phase on the main guitar and of course when I played it to John, he started laughing, because he kind of knew exactly….you know, he was imagining, “I bet I know where this came from!” It’s a song that really relates to the story of the main character -- he’s going through all of these changes and he’s thinking about how he went from having really long hair and realizing he’s going bald and shaving his head. He’s thinking, “It’s just a phase I’m going through,” with a heavy dose of reality, which is the whole contrarian approach to mixing the guitar and having a little bit of a private joke between me and Cuniberti, by being heavy handed with the phaser.

You’ve been making records long enough that you know that there are records that we hear now today that they sound of a time and they fit the spirit and the era where they were created. Are there certain things along the way that you’ve kind of avoided, just because you have the sense that it might end up making the record sound really dated at some point?

That’s a very good question. I think that we probably go through that a lot while we’re building tracks or in the overdub phase. I believe that all of the musicians that you invite in are having that internal dialogue. You know, they may not vocalize it. I think in a way, the producer, it’s his job to create the environment where people feel either free to put anything on there that they feel at the moment is the right way to go, regardless of repercussions years later, or to direct them with firm guidelines, like, no crash cymbals on this album, or we’re never using tambourine again -- you never know, sometimes albums are like that.

A good example is a song called “If There Is No Heaven” and the demo was really rough. It just had this crazy guitar that for some reason, I don’t think I tuned it while I was putting down the demo version of it. So it was already hard for them to listen to. But I kept saying, “I’ll redo these parts and it will all sound great.” It had this really distorted bass part on there that I wound up keeping for the album. When I showed it to everyone, I told them the whole concept of the record, which they thought was thoroughly ridiculous.

I’m sure they were just humoring me, but I said, “You know, just imagine that this guy is going through some deep metaphysical questions and he’s thinking back to a crazy time in his life in the early ‘80s,” and I said, “So you know, that’s why the guitars sound like they could be from the Cure or something like that. And this is why the tempo is more mechanized-sounding.” I said, “Forget about what we sound like when we’re on tour, just think about if you were free just to do this one song and it’s about this guy thinking about crazy times that he went through in the early ‘80s. What should it sound like?”

That direction led Marco [Minnemann] to play, which I felt was just like, the most amazing retro ‘80s drum performance. It was really cool. It really helped make that song unique. Because you know, we could have used big bombastic drums or very clean sounding bass, but I had to tell them, “Look, I was in this band the Squares, we were a trio, we were of the time and we had Marshall amps and a crappy [Ampeg] SVT for the bass and this is kind of like what it sounds like.” I think that in a way, that’s the moment where these ideas should be allowed to flourish and you shouldn’t really worry about years later, [that] I may look back on this and say, “Oh, I was being too trendy or not trendy enough or I should have taken the high road and not reflected what was happening around me.” I think that’s called second-guessing, isn’t it?

For sure!

So that’s not good. I think that ultimately, what it comes down to is that if you ask me, I’m the worst person to ask about how I mixed something or some choices that I made for an album in the past. I actually have to let it go. Once I turn it over to the record company, I need to walk away from it and start working on a new project. You know, you just let the audience decide. They’re allowed to like or dislike to any degree, what you do and it’s really none of your business. My business is simply to make the art and that’s what I do and then I just kind of move forward.

You made a big chunk of this record with the guys that you’ve been on tour with, Mike and Marco and Bryan Beller. From your perspective, what do you like about doing a record of material with these guys?

Oh man, Marco, Bryan and Mike are at the top of their game. They are virtuoso players, yet you can get together with them and play like you’re kids. I mean, it’s just like being 13 years old in the basement and you’re just flailing away and the enthusiasm and the fun that we have playing music to me is the most important part.

It’s easy to find people who can read the dotted notes and everything else that goes with it, but boy, every night on stage, you know, for almost two years, we were always smiling and laughing while we were playing killer music and these people were surprising me every day with just some new way of doing something. So I kept thinking as that tour was moving along, I’ve got to make sure that I get these guys in the room with me at Skywalker and see what we can do, see if I can capitalize on their ingenuity, their creativity, their playfulness, as well as the obvious -- their technical abilities.

You know, the technique really helps, especially when you’re thinking about the budget and the timeframe. I only had them for a certain amount of days, because there was Aristocrats music and stuff that had to be recorded and they had a tour -- Mike Keneally had a record to produce. So I had to work around their schedule and you need pros if you’re going to walk into a place and say, “We’ve got 10 days and we’ve got 12 songs and we’ve got to get it done.” So that’s good.

But the real magic comes from their personalities and they are so much fun to work with, you know, they’re unflappable and they just give interesting performances -- and different ones, take after take, which is a dream if you’re sitting there thinking, “Wow, this is going to be great, because I can take this crazy bass performance and put it with that bass performance.” Mike’s going to come in and do a bunch of overdubs and who knows what he’s going to come up with. So I had a great time working with them and I look forward to doing more of it.

The four songs that you did with Vinnie Colaiuta and Chris Chaney, did that happen in the same time frame as well?

It didn’t. If there’s a way to tie it into the whole revelation of the Shockwave Supernova story, I actually had five songs -- the four songs that Vinnie and Chris appear on, plus the song “Lost In A Memory,” were actually five tracks that were I thought completed as we were mixing them for Unstoppable Momentum. But when we got to the end of that, up in Vancouver, Mike Fraser and I were in agreement that the songs weren’t finished from a writing standpoint, although everybody had put in great performances, I just felt there was either too many notes or not enough notes or there was a bridge missing or I I had to take the bridge out or something.

But I was so deep into that project that I couldn’t work on it anymore and I thought, “You know, I’m just going to pull these songs out and work on them some more.” So as we were going through the Unstoppable tour, I kept listening to these tracks and I eventually approached John Cuniberti to remix them. He came up with the same kind of conclusion that Mike Fraser had, which was that we’ve got these really killer songs, great performances, pristine recordings, however, he gave me that same message, which is, “Are these finished? Did you want to add or subtract anything from it?”

So during a break from the tour, I started to look into these songs and I realized that yes, this part, I need to edit it out. These two sections need more melody and more guitar, I’ve got to change that harmony on that song. So four out of the five, we were basically able to do a small amount of work on them and John remixed them and they wound up -- the drum performances that Vinnie puts on these songs are just insane, “Crazy Joey,” “Keep On Movin’,” they blow my mind. And then of course, “In My Pocket,” which has just the slinkiest, swingingest drum groove I’ve ever heard in my life. He just took it right to some new place.

The song “Lost In A Memory” though, I started to think that I had given Vinnie and Chris the wrong direction in terms of the drum beat -- it was very different -- and here’s where it relates to the story, which was that song actually had its roots back in the late ‘80s, around ‘88. It was something that Stu Hamm, Jonathan Mover and I used to jam on. So I had this beat that was stuck in my head since the late ‘80s. I took it home and I said, “You know, that’s what the problem is,” because I start to listen to the tracks without the drums and then without the bass and then without the drums and then without the drums and the bass and I tried to locate, where is the heart and soul of this composition and I realized, I think the drums and the bass are not actually playing the song properly. So I kind of reimagined it.

I did a really goofy drum machine thing behind it and I sent it off to the guys and I said, “I think this is the way to do this song now.” And so, boy, it didn’t take long -- just a couple of hours for Bryan and Marco to completely revamp the song from the drum and bass standpoint. And then Mike and I actually played seven-string guitars on that. I think we just chugged through it. Those were the only things that Mike did on it that were new. But all of the rest of the guitars and keyboards, Mike and I had done two years ago.

I know the last time that we spoke, you talked about how you came down with H1N1 and wrote about 100 songs during that period that you were home and you were sifting through things at the point that we talked. How much of the material on this new album came out of those songs?

Oh, a lot. A ton of stuff. I would say “On Peregrine Wings,” “San Francisco Blue,” “All of My Life,” “Phase I’m Going Through,” “Butterfly and Zebra” and “Stars Race Across The Sky.” I think prior to that, I’d already been working on “Goodbye Supernova,” I’d already been working a little bit on “Cataclysmic.”

They were really in sketchy forms, actually during the Unstoppable sessions and that’s why I didn’t bring them to the sessions, partly because I wasn’t really quite sure where it was going. But yeah, there was a lot of that. I kind of wrote a Chickenfoot album during that period, but a lot of that material now is headed towards being used for my sci-fi animated series Crystal Planet. It’s really interesting sometimes when you write, you don’t really know where it’s going to end up or how it’s going to get used. That was a crazy period -- every day, all I could do was sit with my guitar and play -- that was about all of the energy I had. But it turned out to be a very creative period.

Well, I’m glad you mentioned the animated series. How much of a firm connection does that have with the album of the same name?

Well, you know, it really doesn’t have anything to do with it. [Laughs] It’s really funny. There’s a funny set of coincidences, like we use as the main track, the song “Time,” which appeared on Crystal Planet, but which was originally recorded for Surfing With the Alien and that song has a weird story all on its own. But it saw multiple musicians and producers and engineers working on it until it wound up on Crystal Planet.

And then my partner with the series, Ned Evett, wound up wanting to use the backing tracks for that as the intro and the outro of our pilot. So it fit perfectly with the whole idea of the series, being that it’s traversing hundreds of millions of years past and future on the planet Earth. But the series was originally called TriDivers, which had to do with these future earthlings, aliens, whatever you want to call them, who learn how to fly using these unusual suits and they’re looking to utilize this strange energy source called Tri-X-9. It will take hours to describe that whole thing. [Laughs]

But somewhere in the last year and a half, Ned and I were thinking, “You know, this is confusing to call it TriDivers -- they’re not really the main characters of the story.” So Ned had been using as many song titles as possible for places and character names, ascribing them to the characters drawn in my art book. So eventually we came to the conclusion that we needed to call the series Crystal Planet so people understood that there was a location and that was really where all of the drama was eventually going to come to a head.

And it made it easier for people to understand, so there’s actually no real thought out connection with that album and now, I mean, I have written and recorded so much music for that in the last year and a half. It’s been so much fun just writing songs that last for two minutes that are just outrageous and used to represent things happening on Earth or on Crystal Planet with aliens or regular people. I find it just so creative to be able to have that kind of a canvas to write for.

When are folks going to see this?

We’re hoping that we get enough episodes to present a bundle to everybody as we hit the road in mid-September. So if the writing goes well, you know, Ned is doing all of the heavy lifting. He does about 90 percent of the character voices, he writes the scripts and does all of the animation and I’m just always throwing new drawings and new music [into the mix] and then we have these long conversations where we sort of distill the story. So yeah, Ned’s been working overtime on this and we’re trying to meet our deadline for September.

With all of the strategies and thought processes that you’ve laid out about the animated series and the album, how it all comes about, I’m happy that somebody out there greenlights this stuff instead of sending you off to a psychiatrist.

[Laughs] I know, I know. It is kind of crazy, isn’t it?

You’ve mentioned it a couple of times -- what’s the state of the union with Chickenfoot?

Oh yeah, I don’t know. You know, I just did a benefit here in San Francisco for the Benioff Children’s Hospital with Sammy Hagar and James Hetfield and Chad [Smith] joined us. So you know, there was the three of us, the three ‘Footers there, gentlemen of the Foot, hanging out. But I got the distinct feeling it’s just not going to happen for reasons that are too boring to go into. I’m kind of giving up trying to be the instigator of trying to get another record done.

We talked about it a few moments ago, where when I was sick, I had written and recorded all of the demos for a new record and really just couldn’t get the people motivated to get going with it. So that music has moved on. I had the feeling at the end of the benefit the other night that although it was one of the most fun things ever, you know, being able to play Led Zeppelin with Linda Perry, and being up there with Sam and Chad again, I just got the feeling like they’re not thinking it’s in the cards. So I’m actually looking forward to maybe finding another band to collaborate with.

I started thinking, “Well, that’s what I should do -- I should just move on,” and then if the guys want to do something, I’m always ready for it. I love Chickenfoot and I think it’s one of the coolest things that ever happened to all of us and I’m a bit heartbroken that we weren’t able to work on a couple more albums and tour -- that would have been really great. But you’ve gotta move on, you know, that’s the reality. Those guys have other things to do that are important to them, so I respect it and I’m just moving on, I guess.

I know you and Steve Vai just did another benefit for Cliff Cultreri and I know from talking to you that he was a really key guy in your world.

I was introduced to Cliff Cultreri through Steve Vai. I had sent him a copy of Not of This Earth and told him I was putting it out on my label. Steve said, “Call me,” and he goes, “You know what? I just got a P&D deal from this company out of New York.” He’d said, “I got rejected by everybody except this one company and there’s this guy, Cliff Cultreri, who is going to put out Flex-Able.” And he said, “If they’re going to put out Flex-Able, they definitely want to put out Not Of This Earth -- can I make the introduction?” I said, “Yeah, sure.”

So my wife and I actually drove down to L.A. By that point, I think Cliff had been relocated to the new L.A. office -- the main company was called Important Record Distributors, out of Jamaica, Queens, New York, but they had an office in L.A. somewhere. That’s the first time I met Cliff and it was just like meeting a soulmate. You know, I’m from New York and he was from the Bronx, he was a guitar player and he’d moved onto working in a record company.

He was just one of those great A&R guys who could spot when something was really cool. And he was a great nurturer and facilitator. He really gave Steve and I carte blanche. He basically would argue our case to the president of the label every time we needed more time or more money or we wanted to do what we wanted to do. [Laughs] Steve and I are like that, you know, we’re pretty headstrong.

So Cliff was with us the whole time. Not of This Earth was already recorded, so he helped get that out and he was the one who argued the case for Surfing With the Alien -- I literally had to convince the label that they should let me record this -- they should sign me to a multiple record deal and give me the carte blanche to go and record this thing. I think it wasn’t until right before the eponymous release in 1995 -- that was finally when Relativity and Important was absorbed by Sony and just as that record came out, the label was closed.

It was a very unusual event to have a record come out and no label to represent it. [Laughs] It was a funny thing and it was a record that definitely needed some explaining, because it was such a departure from what had preceded it in the catalog. But Cliff and I wound up just being super close friends. I’m always talking to him. It seems like every two weeks, we’re on the phone talking about guitar amps, pedals, guitars, strings, you know? [Laughs] Listen to this music, listen to that, yeah, he’s been a very strong figure in my career and my life and Steve’s as well, so we’ve done everything we could to help him get through these periods where he’s dealing with just the worst health issues ever and you know, we feel indebted to him.

You'll Never Guess Who's Now Technically Eligible for the Hall of Fame

You Think You Know Sammy Hagar?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock