How Emerson, Lake and Palmer Turned a Kooky Concept Into ‘Tarkus’

It may seem tough to believe now, but back in 1971, Emerson, Lake & Palmer were forced by their label to temporarily shelve their prog-rock adaptation of Mussorgsky’s legendary classical composition Pictures at an Exhibition in favor of Tarkus because the latter – whose first side was a 20-minute suite about a mutant armadillo – was deemed more commercial. It’s one of those phenomena that can only be explained by the handy umbrella phrase, “It was the ‘70s.”

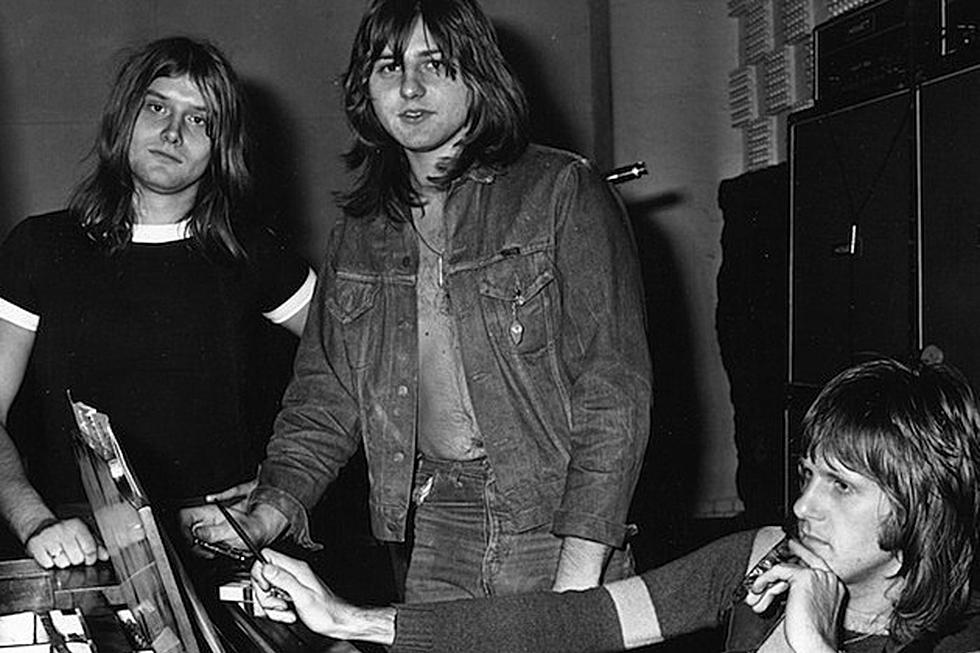

Still, Tarkus arrived on June 14, 1971 as one of the strongest LPs in ELP's discography, and one of the finest prog albums ever. The band was just beginning to grow to its full artistic height, and they hadn’t yet gotten so sick of each other’s ideas that each member required an album side all to himself (as would happen on 1977’s Works Volume 1).

Not that it was all fraternal bliss in the ELP camp: The differences in Keith Emerson and Greg Lake’s musical orientations were already beginning to manifest themselves. Throughout ELP’s career, it was the push-and-pull between Lake’s folk-influenced balladry and Emerson’s classical-minded complexity that helped make the group something special. It was also a perennial source of vexation among band members.

Lake eventually came around to Tarkus’ title suite, hailing it as an example of Emerson’s genius, but he was a hard sell on the seven-part composition at first. The balance of classical and rock was always a tricky negotiation within the band, and Lake viewed the piece as venturing too far into the classical camp for his liking. It’s tough to say whether this was a strictly aesthetic preference, a commercial concern or a more pragmatic issue of instrumental facility for Lake, who lacked Emerson’s classical training.

But Emerson was every bit as much of an alpha male as his bandmate. He pushed his idea, and Lake finally got around to penning some extremely effective lyrics for the piece. But like many conceptual prog works, it’s pretty tough to connect the meaning of the lyrics in relation to any overarching theme, but that doesn’t lessen the song's impact.

If anything, it might even be better this way. After all, from what we’re able to glean of Emerson’s thematic intentions – including William Neal’s artwork on the inside of the gatefold sleeve and the titles of the individual movements – the story is a strange one.

Listen to Emerson, Lake and Palmer Perform 'Tarkus'

It seems to go something like this: A volcano gives birth to Tarkus, a sort of cyborg armadillo with tank treads and turrets on its underside. Tarkus meets a combination pterodactyl/warplane, fights it and defeats it, and then encounters what looks a bit like a reverse Tarkus with artillery in the front and a tail in the back, and leaves it destroyed. Finally, it encounters the Manticore (lion’s body, scorpion’s tale, humanoid face). There’s a Mexican standoff, and after a moment of consideration, Tarkus flees down river.

The screwy saga, when told this way, is a real eye-roller for sure. But when combined with Lake’s sonorous baritone, Emerson’s wide array of organ and synth licks and Carl Palmer’s Energizer Bunny drumming, “Tarkus” becomes one of prog's greatest epics. But there's another half to ELP’s second album, and in contrast to the first part, a couple of tracks display more looseness and humor than the group’s detractors ever imagined the trio possessed. And both of them revolve around a barely-in-tune honky-tonk piano.

“Jeremy Bender” is a tale of America’s Old West that, according to Emerson, began as an attempt to find out what country pianist Floyd Cramer would sound like playing Stephen Foster’s “Oh! Susanna.” “Are You Ready, Eddie?” was a balls-out Little Richard-style rocker based around a catchphrase the band developed while working with the album’s engineer, Eddie Offord.

On the more intense end of the spectrum, “The Only Way” is a hymn-like piece played on a real-deal church pipe organ. But Lake seemingly couldn’t resist penning a lyric that’s pretty much an ode to atheism, replete with Holocaust references that Emerson admits being taken aback by at the time.

Still, when they weren’t at odds, the band could turn out cuts as trenchant as the hard-riffing “A Time and a Place,” influenced by Emerson’s love of Led Zeppelin (and his friendship with Jimmy Page), and the Dave Brubeck-meets-the-apocalypse prog boogie woogie of “Bitches Crystal.”

Look at this way: If they could take an epic about an artillery-laden armadillo and make it into one of prog’s most beloved pieces, it’s possible to believe ELP could accomplish just about anything. That’s certainly the way it must have seemed back in the time of Tarkus anyway.

Top 50 Progressive Rock Artists

Why ELP Hated One of Their Own Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock