Director Dick Carruthers Discusses Led Zeppelin’s ‘Celebration Day’

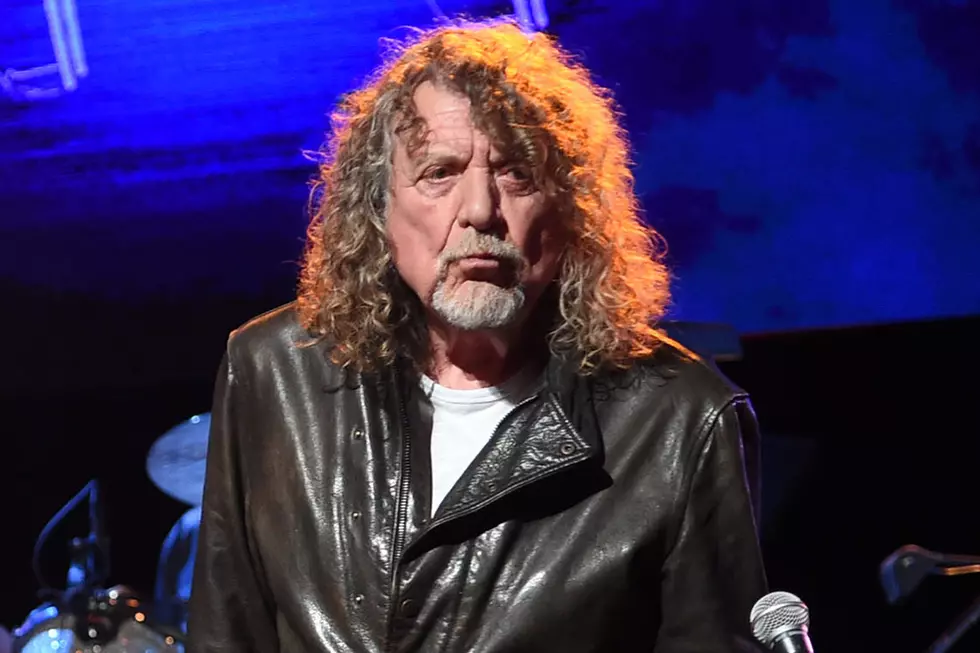

Film director Dick Carruthers has worked with some of the biggest names in classic rock; bands and artists like the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney and the Who were just a few of the stops on his musical resume before he got the call to work with Led Zeppelin.

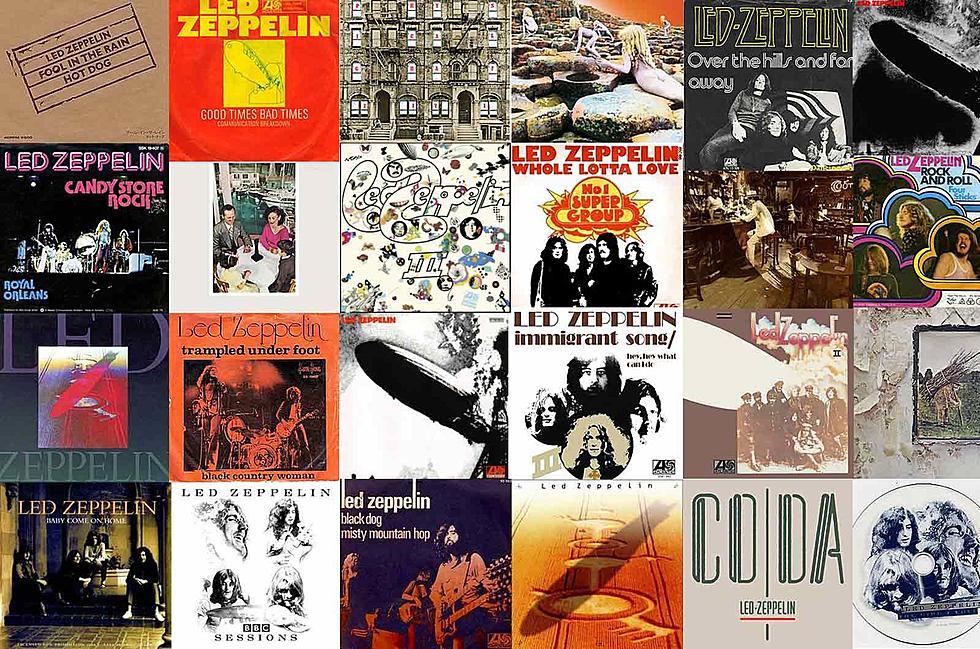

Working first with guitarist Jimmy Page on the 2003 ‘Led Zeppelin’ video release, a collection of previously unseen cinematic treasures from the band’s archives, Carruthers helped to craft a set which has become one of the best selling music DVDs of all time. From there, he moved on to work on the well-received reissue of the classic Zep film ‘The Song Remains the Same.’

Years of working on archival footage of the group for the previous projects would put him in prime position for the ultimate dream assignment, shooting the band live at their one-off reunion performance at London’s O2 in 2007.

The resulting film ‘Celebration Day’ is appropriately titled, as one of the greatest rock and roll bands the world has ever known, came back together for one night only (with drummer Jason Bonham subbing in for the mammoth force that was his dad, the late John Bonham). The chances of a Zeppelin reformation seemed completely against the odds for so many years, so for anyone who was lucky enough to get a ticket to the event, it was a sign that good karma was on their side.

As ‘Celebration Day' reveals, the energy onstage was equally positive and thankfully, it was bottled in both audio and video form for everyone to enjoy. During the course of our conversation, Carruthers is exuberantly enthusiastic while discussing his work with Led Zeppelin, going into great detail about everything that went into making the reunion event the resounding success that it was.

At the same time, he’s fairly guarded when discussing his subjects and the questions regarding possible further activity and reunion shows that have been a relentless topic since the release of ‘Celebration Day’ was announced. While others focus on the future possibilities, Carruthers is focused on celebrating the enduring brilliance of Led Zeppelin’s music which has been captured in the new film.

We spoke at length with Carruthers about ‘Celebration Day’ and dug deep into his work with Led Zeppelin and additionally, the other music legends that he has worked with over the course of his career. In the first part of our discussion below, we focus primarily on the reunion show and the organizational process that brought it all together.

Dick, it’s a pleasure to speak with you. Even knowing the history of this group, it really is something how their popularity remains undiminished after all of these years. It’s a real testament to the strength and quality of the music that they’ve made that built the legacy that we’re now very well familiar with.

The band are really, really popular. Their music endures and they’re amazing. There is no question of that. People hold them very dear and I think the 2003 DVD that we put together that kind of gathered up all of the best of what had been recorded visually and put that together, that, I would like to think, really shows the band in their best light.”

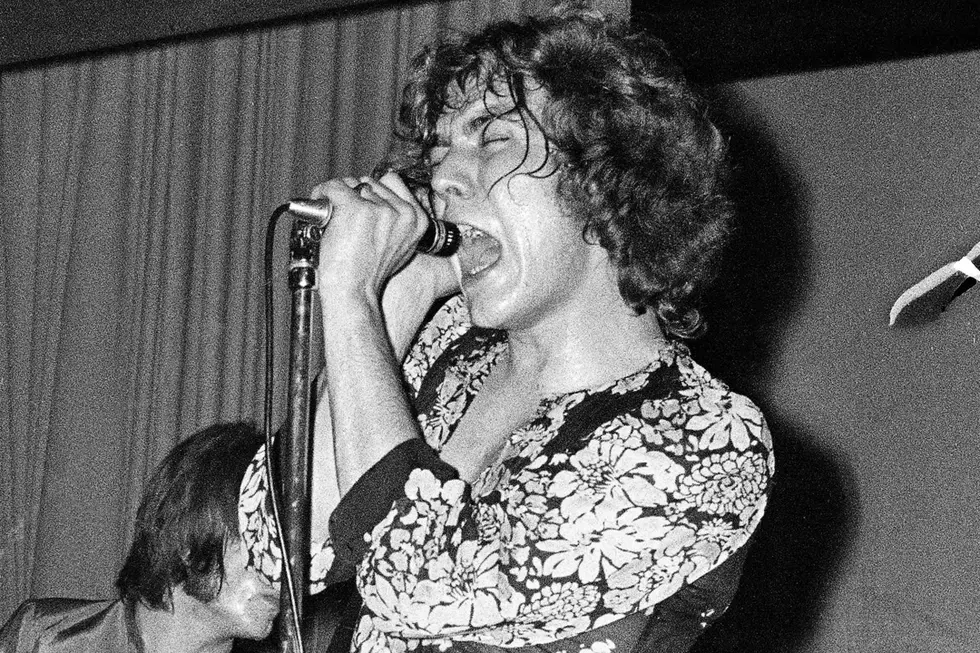

You know [it demonstrated], what it was like with their live performances and something that they’d always felt, famously so, [was] that television couldn’t quite capture it properly and that you really ought to see them live and experience a live gig. And that was to get the full force and the full impact and the whole journey that one goes through [when the band plays live]. Plus the fact that everytime they play is unique - I think all of those things are true. That DVD did put that into context.

We have the new film ‘Celebration Day’ to enjoy now. From the moment that they decided to do the O2 show, was filming and recording it an automatic part of the equation? How much time did you have to prepare for the shoot?

Well, to answer the first part of your question, it absolutely was not, no. In fact, the opposite was the case, that it was very much about putting on this one special night, that they would get back together and do it once. And that if you wished to see this unique thing, then you’d better get a ticket, because that’s the only way you’re going to see it and that was the philosophy and the emphasis behind it from everybody. You know how many people tried to get tickets, which is great, because they was saying that this is the only way you’re going to see this.

So everything that was done was geared towards that one night. So initially, we had an extended period of rehearsals, because Jimmy broke his finger, don’t forget. We had a good period of rehearsal and during that time, I was programming all of the visual effects that I was going to use in the screen, all of the video pieces to accompany the live mix were being made and tested and re-tweaked and the band were rehearsing. We started off in one studio and then basically it was booked, so we had to move, so we moved down to Shepperton [Studios] and had a week or two in Shepperton, putting it all together. But as I say, the emphasis was on this one night and I loved that, I love the adrenaline of that. The greatest things in life, like Neil Armstrong landing on the moon, you don’t have a chance to screw it up and do it again! [Laughs]

There’s that real sense of this is going to happen -- they’re going to walk out and we’re not going to hesitate, we’re going to go for it. Certainly, I can speak on behalf of myself and my team producing it. There was no sense that we were going to play it safe, we were going to go for it. That’s exactly what the band wanted. In a sense of how we moved the cameras, how we vary the shoot for each song and the different looks and feels that we were going for. It’s possible to just point the camera, lock it off and leave it or there’s the possible way of really weaving together quite a complex fabric of visionality, which is exactly what we went for.

That’s the thing, that’s what I love doing and that’s the whole idea with shooting live shows, that there’s no room for hesitation and no room for doubt. But at the same time, you do need to leave room for spontaneity and improvisation and some change of direction if things happen. It is a live, organic, thing and there was plenty of that.

So we had a good period of rehearsals, with all sorts of elements of improvisation and so on there, but only during that period of rehearsals, from a technological point of view, was the point made to say “well, you know, we should record this.” You know, just to get it into the can, lock it in a box and maybe open it another day. But we were all focused on the night of the gig and everything that had to be done. A lot of the way we were doing things technically was quite complicated. There was a lot to play for and a lot of reputations on the line, so nobody was really thinking beyond that. Nobody.

I know there was much talk of many things after that, but at that point in time, it was focusing on the gig. There was just a sense of “well, we should record this and if we’re going to record this, let’s do it right.” It was made very clear to me by everybody involved saying “look, we’re not saying this is going to be a DVD, but if you’re going to record it, you’re going to do it right.”

What would you do, what would you add [and] what do you need on top of what you already have, to shoot for the show? Because the shoot for the show, we had this huge screen and I had quite a lot of cameras and some nice toys and my top team all together and I had this wonderful mixing desk that had all of these high-def effects which we were using to full effect. So to add to that, we didn’t really need to do an awful lot, other than saying, “Well, we need to light the audience and we need to add a few more cameras as well, to get in some wide shots.” Even that’s not especially important, because as you’ll see in the film, we don’t really use wide shots or audience shots very much, because it’s never as interesting as what’s going on onstage.

So it was essential to add a few more things and just shoot it and get it in the can and we’ll lock it in a box. And that’s what was done. And from my previous experience of working with the band, I didn’t expect there to be any hurry to even look at it, because as the previous materials that I had worked with them on had shown, they will sit on something for up to 20 years and then say, “Okay, we feel like now’s the right time to work on it and put it out.” So that was it and it went away. Of course, that’s all sort of history now, because here we are talking about the release of the film in cinemas, the DVD and the [deluxe] DVD with the entirety of the rehearsal on it as well, which is amazing as a contrast to the film. Did you know that was there?

I actually was going to ask you how much of that would be included on the DVD, because I saw that there would be rehearsal footage in the bonus materials. That’s great.

The whole rehearsal - start to finish. A lot of people are just going to be so very, very happy. There was one copy of it, which happened to be in my DV camera. On that particular rehearsal day, it was sort of a dress runthrough and it was decided that they were going to play the whole set from start to finish with no interruption. So I just stuck a camera, not quite a full professional camera, on a tripod next to me, for a wide shot. I think it was like, “Yeah, we want to look at this afterward, so let’s have a recording of it.” And that was it and it never even got looked at. [Laughs] So there was one standard definition copy of the entire rehearsal and it came down to, “Well, hey, this is going to go out, what else have we got?” Because we didn’t have much other stuff -- we had a bit -- I had some bits of the soundcheck at the O2, some bits around the O2, but none of it was that great, because it so completely paled into insignificance compared to the actual musical performances of the band. So that’s really what it’s all about.

We had this one copy of the rehearsal, so we’d looked at it, synched it up with the audio, of which there was only an existing stereo mix and matched it up. There was discussions about, “Well, you know it could be four or five songs -- let’s listen to it and see if it’s any good.” And then the idea gradually emerged amongst the band and everybody - you know it wasn’t a slam dunk, as you might say, it was more like, “What if we put the whole thing on?” And I said, “Well you know, that would be amazing. That would be truly amazing, courageous, generous, honest, confident -- it would just be an amazing thing for fans, to put the whole damn rehearsal on, warts and all.”

It would mean that it definitely wouldn’t fit on one DVD, it means that we suddenly go to two DVDs, but hell yeah, let’s do it. There was a period of time when it wasn’t definite and in the end, everybody said, “Hell, let’s just do it -- as a gesture to the fans.” And really, understanding how it sits in counterpoint to the main concert, because of course, the main concert, we spent months and months working on editing and getting everything just right. The rehearsal, it was like one shot, nothing else! [Laughs]

It’s brilliant and of course, because of the way they play, it’s sort of the same, but also totally different at the same point in time. There are some beautiful moments in that rehearsal where Robert shouts out, “Hey! Hey! Are we recording this?” and Mick [sound engineer “Big” Mick Hughes, well known for his years of working for Metallica] yells, “Yeah!” and Robert says, “Fantastic!” There are some great moments in the rehearsal in between the songs as well.

When it came to the filming of the actual gig, what did you hear from the band as far as what they wanted to get out of it? What were they hoping to capture, besides just getting it on film?

Well, obviously there’s a sort of default trust. One thing that they had encouraged was to really capture what they were playing. There’d always been this sense of that never really being captured in close-up. There was a huge screen and of course we’ve got high-definition cameras and incredible lenses now. So there was a sense of, “Yes, I do want it to be filmed.”

I did a film for the White Stripes a couple of years ago called ‘Under Blackpool Lights,’ which will become significant when you see the Zeppelin film, because there’s a lot of Super 8 in that as well, because I’m a big fan of using it. When we were editing the White Stripes film, there was a shot I had of Jack White on his Wah-Wah pedal, doing this thing that he does with his feet and when we were doing this little review of it before it was finalized, Jack said to me, “Hey, can you actually take that shot out -- I kind of don’t want people to see how I make that sound,” which was really funny and I said, “Yes, of course -- fine, if you want it out!”

I remember saying this to Jimmy -- obviously they know each other -- and I said, “Jimmy, is this a Jack White thing -- do you not want me to show your pedals, do you not want me to show how you do what you do with a theremin or with a violin bow?” He said, “No, absolutely, I want people to see what I’m doing.” This even extended into the ever-present debate about how we use the big screen and what the impact of it would be. During the bow sequence and the laser sequence of ‘Dazed and Confused,’ should there be any pictures in the screen at all and the answer is, “Well yeah, because Jimmy wants people to see what he’s playing, so we have to divide it off into sections.” There’s very little in both the show and the film that wasn’t sort of thought about and programmed and deliberate. A lot of thought went into it.

They wanted everything to be deliberate and bold and powerful and effective, to display technical and musical mastery of what their game was. But at the same time, they were certainly allowing for improvisation and allowing for looseness to be in there. So that was one key thing -- I do go close on what everybody is playing a lot. When you have a shot of a drummer, it’s much more easy to see what he’s doing, obviously. But with [bassist] John [Paul Jones] and Jimmy, you've got to get right in there and really show what their hands are doing. But beyond that, show where they are geographically, when Jimmy is over by his pedal board and he’s changing things -- you’ll see how many times he switches the switch on his Les Paul, which is a lot. So when he did do that, when he was changing the tone or sound of it, I tried to often make sure that I feature it, to show what he’s doing.

[Especially for] key Zeppelin moments, like when he switches between the six string and the twelve string in ‘Stairway to Heaven’ and what he’s playing with ‘The Song Remains the Same’ after it -- his guitar moments and how he plays them are key. But beyond that, how they look at each other, when they turn around. There’s a lot of times when they gesture to Jason to come back in with a fill or when a song changes gear and John more than anything, looks at Jason. They all look at each other and often it’s complementing their work, in each other’s playing [and] they’re watching each other’s body language to see where something’s going to go and take off or change or mutate. They really do watch each other and the communication between them is something that I really made a point of featuring in the film. I think it will bear repeated viewings, I’d like to think, because you’ll see that, you’ll see all these little nuances. Sometimes, the gestures are, “Where are we? What are we doing next?,” and sometimes at the end of songs there’s like “Whew, we got through that one,” and “Hey, that’s been alright -- I think that was really good.” All of that is in the facial expressions and in the way that they do it and it’s great.

You’ve worked on a lot of footage of the original band. With them playing with Jason at this gig, what are the differences that you saw, having seen so much of the original lineup?

I think the differences, first of all, as I said, were that we could go a lot closer and forensically look at what’s being played. It’s pretty much an accepted fact that these guys are musical geniuses and masters of their game. But to actually show how that works, it’s like, we all know [that] you can look at pictures of a Ferrari from the ‘70s and ‘80s and know it’s an amazing car. But this time, we were able to get a camera inside the engine compartment to see what they can do and how it was done.

Also, because we had a lot more cameras, that made a big difference [in being able to] cover every single shot. Because I think with the way that things used to be shot in the ‘70s, they lingered shots a lot more and [now] we can move the cameras and give the shots of the band more of a dynamic resonance with what they’re playing. I think that’s most of it, in comparison to some of the others.

Like the Earl’s Court stuff that I put together back in the day, all that existed of Earl’s Court was a line cut. So what you saw is what you had. There was no other cutaways -- there was nothing. We had to come up with some trickery, just to make it have another texture. Funny enough, we did that with some Super 8 [film], to give it another layer of texture. That’s all we had then. Whereas in this instance, we had 10 to 12 cameras, three Super 8 film cameras in the crowd, all operated by experts, so we had a lot of shots to choose from.

The variation was there and there were a lot more choices to jump between framing in the angles and to piece it all together. It’s a more intricate jigsaw puzzle. Like a kid’s jigsaw puzzle might have nine or sixteen pieces, but one of those jigsaws that you do on holidays has three thousand pieces! It doesn’t mean to say that the picture that the jigsaw makes is that much better than the other one, but it’s a much more complex piece.

Today’s video work sometimes gets criticized for having too many cuts and being too busy, instead of letting the scene just play out, which was the way it was with some older video productions. From your side of things, how can you manage to keep something from going too far over the top? Because the commentary seems to be that it feels like everything has to be like an MTV video and a lot of times, the average fan just wants to see the concert.

Yeah, I think that it’s true that an awful lot of stuff is overcut these days, refining the discussion to live music coverage, not necessarily [just] concert length features per say and it is true that it’s overcut. In some instances, that’s entirely musically justified. But actually no, it probably isn’t. I think that if you cut something very, very fast, live or in post-production, it creates an overall impression. And that overall impression may be good. It may fit with the band. There are certain bands like Muse or the Prodigy, for example, where some of my colleagues have made feature-length films of them and just absolutely cut it to ribbons. And the overall impression of it is great -- it’s quite hyper. But it doesn’t really give you an insight into what it was like to be at the concert, into how the band plays and into the personalities of the band off-stage and so on. It’s all a bit of a mad mashup.

You’re also right in saying that one does see that methodology applied far too often and inappropriately. There’s also a sense that if the lights are flashing and the cameras are shaking and everything’s cut to ribbons, that it somehow has an incredibly dynamic vibe to it and obviously that is not true. In fact, it’s dressing something up in the emperor’s clothes.

Was I aware of that going into this? Of course, absolutely. There’s a need to get the stylistic bent and the overall narrative and the individual pacing of songs just right. There’s also, because of who it is and what it is, it brought a sense of a classic feel in a modern setting, which it was. So at times, there are a few mashups -- like the vamp at the end of ‘Dazed & Confused’ springs to mind and bits of ‘The Song Remains the Same’ are quite fast cut. There are plenty of times where we just sit on it and let it roll. So it does have a classic feel, but it is modern and there is quite a lot of shots in it, but they are entirely musically justified. Often, there’s so much going on musically and so much going on [with] where the band are and how they’re communicating, that you want to jump around them.

Now there was a time during the editing stage where it was definitely cut too fast, because we shoehorned too many shots in there, because we had so many good shots. It’s only when you get to that stage and you show it to the band and you can say, “Right, well we’ve got all this -- let’s slow it down a bit and let’s look at how ‘Ramble On’ goes into ‘Black Dog.” Alright, well ‘Ramble On,’ it’s nice slow verses and it needs a bit of madness in the chorus. And then you get to ‘Black Dog’ and you’ve got these kind of acapella moments and then these mashups. So that’s where you start jumping stuff around.

Speaking as a director who edits, you can have a sequence that’s very, very fast. You only need to take out a couple of shots here and there and it slows it right down. So I would be disappointed if anybody thought that these youngsters had ruined it. But you’re going to get the diehards that say, “Oh, this is all crazy -- why can’t we just watch the concert -- I’d like one camera at the back fixed and locked off” and the answer is that you get it -- it’s in the rehearsal, there it is! [Laughs]

From seeing it, nothing really feels over the top.

It is absolutely deliberate. Everything has been handcrafted. It wasn’t like we spent a day on a song and said, “Okay, that’s done,” and didn’t really look at it again. Everything has been constantly revisited to try and get it just right [not only] individually in the song but [also] in the context of what precedes and what follows it, because the whole thing has to have light and shade. It has to be watchable as a two-hour opus. There are certain other rules that I have about the film is that you don’t really want to be distracted by seeing lots of other cameras and cameramen in shots. You’re going to inevitably see them now and again, so we shouldn’t try and hide them. There shouldn’t be any fakery to it.

But at the same time, you don’t want them pissing you off either. So there’s plenty of shots that were amazing, but had an ugly lens in the back of them or movement or something that distracts your eyes, so we dinged them. When you see the film, you’ll see occasionally, some cameras, but very, very few - it’s kind of invisible. We never edit so fast or do something that’s cut with a beat or a drum roll -- again, if you watch a lot of music TV, you do see that sometimes. We never do that, because that is breaking a golden rule of mine, which is inserting the director into the narrative. If you become part of the story and you’re saying, "Hey look at me, I had loads of cameras set up, look, I can go cut cut cut cut cut,” to try and punctuate the music -- even if that idea was coming from the right place, what you’re doing is reminding everybody that there is a director’s hand in this and that there were cameras there recording it and that you’re not watching them on the night that you’re being presented something that ultimately is being taped. You’re being presented a polished reversioned version of reality. There are certain directors out there that do that as their default setting and to be honest, I find that dreadfully egotistical, because it’s like saying that there isn’t a fidelity or an honesty towards the band and its music. It’s kind of “look how flashy I can make this.” I think you’re telling entirely the wrong story there and in the wrong way. So having dissed all of my contemporaries ... [Laughs]

Of course we don’t do that. I’ve had the great privilege to collaborate with and work with this amazing, amazing band for over 10 years now, in a variety of different hats, shall we say. I’ve become acutely aware of so many things -- their personalities, how they play, their musicianship, what they like and don’t like -- their reaction to seeing themselves. You see, that’s the key. It was key 10 years ago, when we were putting together all of this other stuff [to recognize and incorporate] their reactions to seeing themselves and how they stand and how they play and what they do and what they look like. So I’m exceedingly aware and sensitive to all of that.

When we were putting this film together, I was able to bring all of that into play and know that no matter how good a shot was, why we should show that or why we shouldn’t show that and [recognize] when we’re going off piece compared to when we’re staying with where the music is. Jimmy might do a gesture when he’s just finished this note, which is a sustained note and he’ll look out over the crowd and move his right hand from left to right over the crowd and then he’ll just jump back in or what he does, just before he hits another powerchord -- he’ll do this move just before the powerchord. His neck will move while there’s a drum fill, so there, I’m thinking, do I show the drum fill, or do I show Jimmy’s body language as the drum fill plays? All of that is looked at and worked out and thought about and ultimately, there has to be a fidelity to what the music is and what they’re playing and how they’re playing it and I would consider it some degree of failure if anybody watched it and was aware that it was a film. It shouldn’t be, it should be an invisible thing.

There’s a few special effects in it, but not many. There’s a few freezes and there’s a few bits of slow-mo here and there - there’s a few grade jumps. It’s got a little sprinkling of modern special effects wizardry to it. So does the sound -- the sound has a little bit reverb here and a little bit of chorus there and a little bit of panning left and right, backwards and forwards and front in the cinema mix. It’s got polished bits there, but I would be upset if the illusion was broken, because you should immerse yourself, whether you watch this on your TV from a DVD or Blu-ray, or whether you watch it in the cinema as a shared experience, it should be immersive. It should make your eyes dance and make you want to stand up and play some air guitar, for God’s sake! It really should. I’ve been very careful to not break the immersion of that, by doing anything that’s either too fast or too flashy or certainly, God forbid, anything incongruous. It’s all quite hermetically sealed into what the night was.

I’m sure there were probably a few goosebump moments for you during the gig, if you even had the chance to really enjoy it in the moment.

Well, you’ve got to remember that I’m actually cutting it and calling it and operating a desk with lots of special effects. It’s like flying a jet plane. So you don’t really have time for a goosebump moment. You don’t really have time to kind of look up and pinch yourself or have one of those Muppet moments. You know when the Muppets touch a camera and just go “whoo!” I had no time for Muppet moments! And that’s what I mean about it feeling like 10 minutes long, because you just do it and then it’s, “F--k! Wow! That just happened!”

But were there any moments where I was instantly aware that something amazing just happened, the answer is “yes.” Again [with each song], you’re playing three dimensional chess at 500 miles an hour with your hands and your eyes and everything, so you can only sort of have a breather at the end of songs where you say, “Right, guys, it’s this next and that was great and that was great.” I think there’s just certain songs that were just incredible. ‘For Your Life,’ I always quote ‘For Your Life’ as one of the highlights, just because it’s such a unique thing, [because] it was a song they’d never played live before, apart from in rehearsal. ‘Rock and Roll’ and ‘Whole Lotta Love’ are brilliant -- they’re just kind of mad. I think the real technical precision of what’s going musically and how we had to shoot it and capture it and change and shift gears with the band. I’d have to move my cameras in different ways around the stage to capture what was going on and capture some of the off-piece moments and actually cut them to the screen and nail them and get off them and capture it all right. There was a couple of places where everything absolutely slotted together.

‘Kashmir’ [was another one] and when you watch it, what I was doing that night on the screen with ‘Kashmir’ was very, very simple, compared to the other stuff. ‘Dazed and Confused,’ I was doing three mixes across the screen, because the whole point of that was that I wanted to have John on the left, Robert in the center and Jimmy on the right and depending on who was playing, mix in and out so I’d have three Johns or three Jimmys and all three of them with everything, so I’m using three banks of the mixing desk to do that and obviously, Jason would also be in there on the drum fills. So that was very complex, getting everybody to get that just right and then shifting gears.

But in ‘Kashmir,’ because there was more of a visual presentation with some ethereal bits of Robert, what I was doing there on the night was nowhere near as taxing. But then playing ‘Kashmir’ on the night, [watching Led Zeppelin perform that one] was a total goosebump moment. And ‘Kashmir’ just builds and builds and builds and then it gets better and then the next drum fill sounds even bigger than the last one and then the next big chord and so on.

Something else about ‘Kashmir’ to bear in mind, when you said how did it [shooting the band live] compare with the old archival footage? There was an absolutely amazing thing that had never been captured or even seen or even amongst some of your readers, not even known. Where the hell is the bass coming from on certain songs? John Paul Jones plays it with his feet. Now, not a lot of bloody people know that, as he says in his best Michael Caine voice. [Laughs]

But, he does and he plays it very, very well. Without overstating the point, I show it, I cut to it in ‘Since I’ve Been Loving You,’ in ‘Misty Mountain Hop’ and in ‘Kashmir,’ what he is playing with his feet is key to the sound. It’s never really been seen or understood before. But it is now! [Laughs]

More From Ultimate Classic Rock