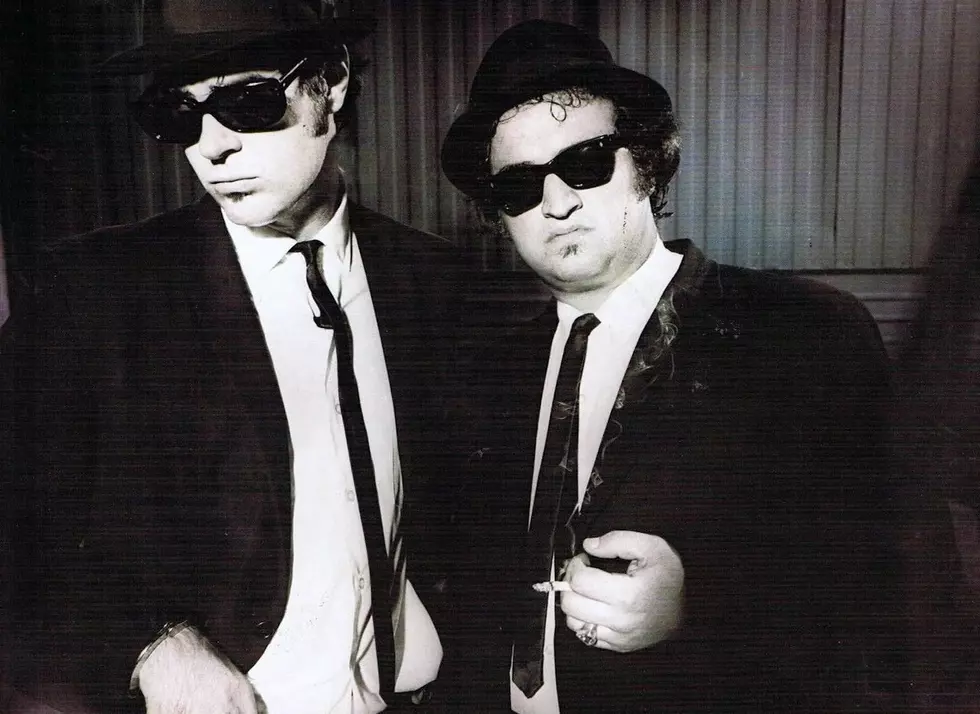

45 Years Ago: Blues Brothers’ Debut Becomes a Labor of Love

When the Blues Brothers gathered to record what would become their smash Briefcase Full of Blues, there was still some question as to whether they meant it or not.

Were comedians-by-trade John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd looking to extol the virtues of R&B and blues during an opening gig for Steve Martin at Los Angeles' Universal Amphitheater? Or simply to lampoon it?

The first hint came with the tough backing group they assembled for the occasion: Steve Cropper and Donald "Duck" Dunn from Booker T. and the M.G.'s; Matt "Guitar" Murphy, a former Howlin' Wolf sideman; Willie "Too Big" Hall of the Bay-Keys; and Steve Jordan, who would later work with Keith Richards, among others.

"The Blues Brothers came off as a genuine article because we had Cropper and Dunn and Matt Murphy – those three magnificent Memphis guitar players," Aykroyd later told Blues Blast. "Murphy played with James Cotton, and Duck and Steve played on all those Stax/Volt records. That combination was a powerhouse that was not to be duplicated, a Chicago/Memphis fusion band. That’s what the Blues Brothers was and that’s what really made it work. They added legitimacy to our enterprise."

READ MORE: 'Saturday Night Live' Weekend Update Anchors – Where Are They Now?

But Briefcase Full of Blues, released a few months later on Nov. 28, 1978, wasn't powered by their participation alone. Despite how entertaining it all sounded, Belushi and Aykroyd took the whole thing very seriously.

"In the early days, a lot of the press reported that John and Dan were making fun of the music," Cropper said in 2014. "Duck and I read that and said: 'What? We couldn't make fun of our music.' We had to do some interviews and let them know how serious they were. Dan studied hard to learn how to play harmonica. John had been a rock and roll drummer long before he became famous as a comedian. It ended up being one the best collections of blues musicians I've ever seen."

Listen to the Blues Brothers' 'Messin' With the Kid'

Blues Brothers' Tribute Sells Millions

What resulted was an irony-free celebration that became a platinum-selling No. 1 smash. (Belushi and Aykroyd eventually pitched in an additional $50,000 of their own money when the label advance failed to cover recording costs.) In no small way, Cropper adds, the Blues Brothers' energetic recasting of these classic songs helped them remain relevant through a period when the Bee Gees and punk were in ascendency.

"We had to keep this music alive, to educate a younger generation on this music," Cropper argued. "Soul and blues and jazz, those are the greatest staples that the American people have invented. But there's more to it than that. Eddie Floyd [who continued as a touring member of the Blues Brothers Band for decades] and [the late Stax drummer] Al Jackson, they told me a long time ago: It is also about entertaining people. You are not going to be interesting to people just standing up there. They can hear that on the radio. You've got to get them swinging and swaying with you."

That led Cropper to a sudden realization: If anything, the Blues Brothers had started out a little too seriously.

Aykroyd, a Canadian, first discovered American blues – not Belushi, a dyed-in-the-wool rock guy who grew up outside of Chicago. They became fast friends after meeting on the set of Saturday Night Live, where they first tried out the Blues Brothers personas. Aykroyd would play these old records, and Belushi began to discover the impetus for favorite bands like Led Zeppelin and Grand Funk Railroad. He was hooked.

"It changed my life," the late Belushi once told David Scheff. "As a white kid from the suburbs you just didn't go into neighborhoods where blues was. I didn't like disco, and I was getting tired of rock. I mean, how many Rod Stewart albums can you buy?"

So, he and Aykroyd initially began working up a set of gritty songs associated with Junior Wells, Big Joe Turner and the Downchild Blues Band. Of course, history tells us that the Blues Brothers rose to quick fame singing something far more rambunctious. That's where the Stax guys come in.

Listen to the Blues Brothers' 'Hey Bartender'

'Soul Man' Was Suggested by Steve Cropper

"In the rehearsals in New York," Cropper told Michael Berry, "I came in late. Duck grabbed me and he said: 'We're cutting a lot of good stuff here, rehearsing a lot of good stuff, but it's all kind of blues stuff — nothing commercial.' He said: 'You need to go in there and talk to these guys.' I said: 'OK, give me a chance to see what's going on.'"

Cropper made a key suggestion. "I looked and John and I said: 'Have you guys ever thought of doing something that you guys could, like, dance to?' And he said: 'Like what?'" he added. "And I said: 'Like Sam and Dave. They had great records, but they were known as dancers. They could really get the house going.'"

The band launched into "Soul Man," "and they started dancing and clowning around and all that," said Cropper, who famously appeared on the original Sam and Dave session. "Everybody was laughing and having a big time."

READ MORE: Rock's Biggest Moments on 'Saturday Night Live'

That deft balance of rootsy realness and hip-shaking rhythm helped Briefcase Full of Blues to out-of-nowhere double-platinum sales. The album spawned a pair of Top 40 songs in "Soul Man," which went to No. 14, and the No. 37 single "Rubber Biscuit," earlier recorded by the Chips. Later, there was a smash – literally – hit movie, too.

Unfortunately, Belushi was felled by an accidental overdose a couple of years later, leaving Aykroyd to continue alongside Belushi's brother Jim and John Goodman, among others.

The Blues Brothers went on to release more than a dozen albums, including compilations and live sets, while providing an important new support system for the original composers of the songs they covered.

Listen to the Blues Brothers' 'Soul Man'

How the Blues Brothers Helped Early Legends

That was actually at Belushi and Aykroyd's insistence. Atlantic, the label that released Briefcase Full of Blues, first suggested that they contact legacy artists like Floyd Dixon, Cropper, Isaac Hayes and Donnie Walsh from the Downchild Blues Band with an offer of 50 percent of the publishing royalties.

"John and I refused, which was pretty unusual at the time," Aykroyd told Darren Weale. "We've had no share in any of the songwriting royalties on the eight records. We have a little for the mechanical royalties, the voice work, but that's a pittance since Steve Jobs and Apple ratcheted down the value of music and it's all digital. All the publishing royalties went to the original artists. We could have owned a part, but we did not grab a share of it. That's not right."

Artists like Dixon, who composed "Hey Bartender" from Briefcase Full of Blues, were suddenly receiving the largest royalty checks of their careers. That only added to the sense of old-school camaraderie that kept Cropper involved with the Blues Brothers long after Belushi passed.

Curtis Salgado, a soul-blues shouter who was a huge behind-the-scenes influence for Belushi, ran into Floyd Dixon years later and asked him about the windfall.

"I go 'It's none of my business, but how much did you get?'" Salgado said in 2015. "Floyd says, '$78,000, the most I ever got.' I think, 'Enough to buy a house!' I asked, 'What did you do with it?' He looks into the sky. This was on the main stage at the Chicago Blues Festival. He says, 'I put it all on the horses. I had a wonderful time, man.' That's a Blues Brother right there. That's the real shit."

The Dixon story took a while to get back to Dan Aykroyd. "I didn't know that," Aykroyd told Weale. "Did he get his royalties? I'm so pleased."

The Band Behind the Blues Brothers

Gallery Credit: Bryan Wawzenek

Did ‘SNL’ Finally Confirm the Fifth Beatle?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock