The Beatles Take a Flight of Fancy With ‘Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!': The Story Behind Every ‘Sgt. Pepper’ Song

The Beatles' strikingly vivid "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" found inspiration in the most unusual of places. For John Lennon, it was a framed 19th-century poster for a Victorian-era circus; for producer George Martin, it was an offhanded comment about making the song as visceral as possible.

Lennon stumbled across the poster for Pablo Fanque's Circus Royal while browsing at an antique shop with future Apple Records employee Tony Bramwell near the Beatles' hotel at Sevenoaks, Kent, where they were filming a promotional film for "Strawberry Fields Forever." William Kite, John Henderson (the "celebrated somerset thrower!"), Zanthus ("well known to be one of the best broke horses in the world!!!") and the others were real performers in a troupe managed by Fanques, said to be Britain's first black circus owner. Captivated by its long-ago sense of wonder, to say nothing of its fantastical use of language, Lennon hung the poster in his music room at Weybridge for inspiration.

"It's a poster for a fair that must have happened in the 1800s," Lennon told David Scheff in All We Are Saying. "Everything in the song is from that poster, except the horse wasn't called Henry. Now, there were all kinds of stories about Henry the Horse being heroin. I had never seen heroin in that period. No, it's all just from that poster."

At some point along the way, Paul McCartney said he joined in the creative process. They continued tweaking, as "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" came into focus. The benefit shifted from Rochdale to Bishopsgate, in order to rhyme with "don't be late"; the circus also became a fair, so it would match the line "will all be there." The title was lifted word for word – along with key phrases like "over men and horses, hoops and garters," "somersets on solid ground" and a "hogshead of real fire."

"I read, occasionally, people say, 'Oh, John wrote that one.' I say, 'Wait a minute, what was that afternoon I spent with him, then, looking at this poster?'" McCartney later recalled to Rolling Stone. "He happened to have a poster in his living room at home. I was out at his house, and we just got this idea, because the poster said 'Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!' – and then we put in, you know, 'there will be a show tonight,' and then it was like, 'of course,' then it had 'Henry the Horse dances the waltz.' You know, whatever. 'The Hendersons, Pablo Fanques, somersets ...' We said, 'What was 'somersets'? It must have been an old-fashioned way of saying somersaults. The song just wrote itself."

The Beatles worked through seven early takes on Feb. 17, 1967, just days after Lennon first saw the poster on Jan. 31 - and, coincidentally, the same day "Strawberry Fields Forever" was released in the U.K. as a double A-sided single with "Penny Lane." McCartney ended up contributing one of his more expressive bass lines, while Ringo Starr's eruptive drum rolls before each verse – not to mention his merry hi-hat smashes – only added to the heady atmospherics.

Three days later, Martin began work on a soundscape of carnival music that Lennon had requested in order to complete "Mr. Kite." There wasn't a lot to go on, as Lennon – an untrained musician who worked on feel – once again hadn't gone into much detail with his legendary producer.

"In terms of asking me for particular interpretations, John was the least articulate,” Martin remembered in Anthology. “He would deal in moods. He would deal in colors almost – and he would never be specific about what instruments or what line I had. I would do that myself." In regard to "Mr. Kite," he remembered Lennon simply saying: "'I want to be in that circus atmosphere; I want to smell the sawdust when I hear that song.' So, it was up to me to provide that."

Martin got to work. He'd ultimately add harmonium, organ and glockenspiel, playing some instruments at half-time then speeding them up to bolster the festive atmosphere. But there was still something missing. During a weekend off, he settled on Beatles sound engineer Geoff Emerick's bold suggestion that they return to a concept earlier employed for the brief two-bar brass solo on "Yellow Submarine": Splicing together vintage sounds, they'd create a swirling effect – a veritable kaleidoscope of music every bit as evocative as the lyric.

"I knew we needed a general mush of sound, like if you go to a fairground, shut your eyes and listen: rifle shots, hurdy-gurdy noises, people shouting and – way in the distance – just a tremendous chaotic sound," Martin said in Mark Lewisohn's indispensable The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. "So, I got hold of old calliope tapes, playing 'Stars and Stripes Forever' and other Sousa marches, chopped the tapes up into small sections and had Geoff Emerick throw them up in the air, reassembling them at random."

In all, 19 pieces of tape were used for this 30-second bit of sound. But on the first try, Martin still wasn't satisfied. "I threw the bits up in the air but, amazingly, they came back together in almost the same order," Emerick told Lewisohn. "We all expected it to sound different, but it was virtually the same as before! So, we switched bits around and turned some upside down."

Additional sessions were held on March 28, 29 and 31, the second of which saw Martin mix in the fairground snippets. Lennon seemed to be of two minds about the finished product. "I hardly made up a word, just connecting the lists together – word for word, really," he told biographer Hunter Davies in 1968. "I wasn’t very proud of that. There was no real work. I was just going through the motions, because we needed a new song for Sgt. Pepper at that moment."

In time, however, Lennon came to share fans' enthusiasm for this remarkable outburst of psychedelic invention. "It's so cosmically beautiful,” he told David Sheff in 1980. "The song is pure, like a painting, a pure watercolor."

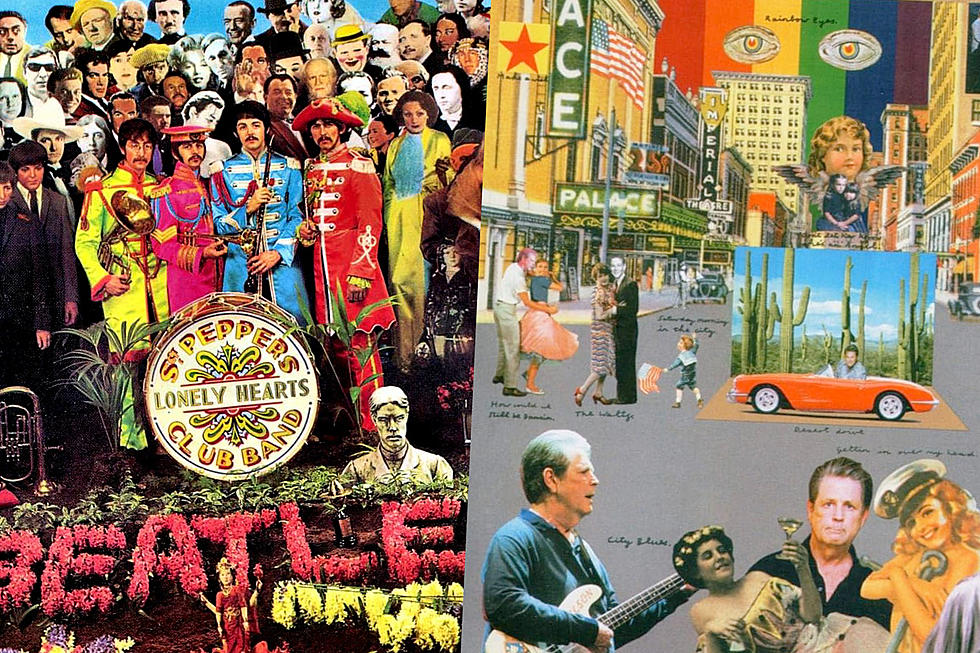

Beatles' 'Sgt. Pepper's' Cover Art: A Guide to Who's Who

More From Ultimate Classic Rock